SIGN UP TO OUR NEWSLETTER FOR DISCOUNTS, PROMOTIONS and PRIZES!

Dead Northern 2024 festival review – The Blair Witch Project (1999) 25 year anniversary screening

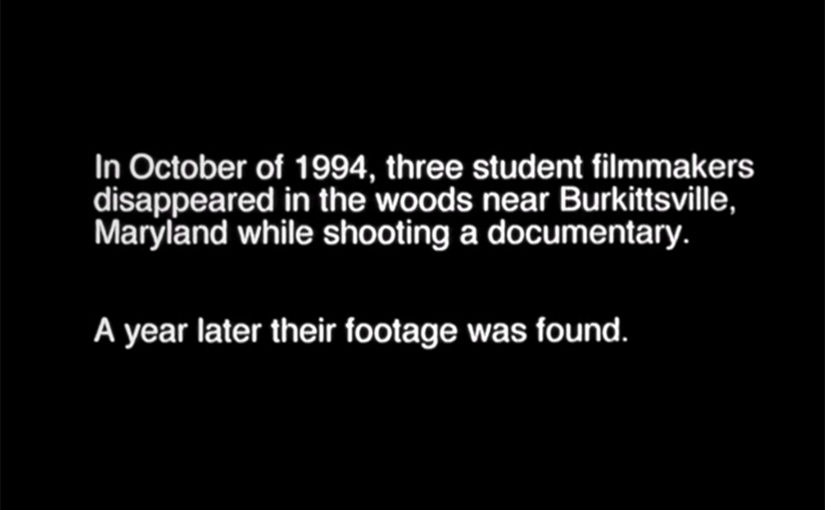

The Blair Witch Project opens with the infamous title card announcing the disappearances of three student filmmakers. What follows is the discovered footage of what went on during the fatal trip, culminating in their mysterious and unexplainable vanishings. Legend has it, the trio’s bodies have never been found…

In 1993, film students Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez began to recognise a pattern – they found documentaries on the paranormal far surpassed the fear factor staged by traditional horror cinema. After years of passing the idea of a scripted supernatural documentary around, they (along with Gregg Hale, Robin Cowie and Michael Monello) started the production company ‘Haxan Films’, which, for those who picked up on this detail, yes, Haxan comes from the infamous docu horror Häxan (1922).

With the production company garnering a small money pot from producing corporate and commercial videos, the crew set ahead to get the ball rolling on the long-awaited pseudo-documentary. The premise of something strange, dark and mysterious being real, particularly within its presentation, is terrifying.

Fiction is escapable and, more often than not, non-threatening past the screen. However, the immersive, replicative, and first-hand perspective of vérité cinema can provoke the viewer to suspend their belief and mediate reality into the fictitious narrative. Whilst the contemporary commonality of reality-coded horror falters the chances of the cinematic events being perceived as real, in 1999, this was groundbreaking and convincing to audiences. As such, Myrick and Sánchez weaponised the diegetic camera brilliantly utilised by previous filmmakers such as Shirley Clarke, Ruggero Deodato and Satoru Ogura and created one of the most infamous horror movies of all time.

At the start of production, the focus characters, Heather Donahue (now Rei Hance), Michael C. Williams and Joshua Leonard, were all informed that this was not an archetypal experience. The screenplay was 35 pages long, but the content was more stage directions, with the directors opting for the dialogue to materialise from improvisation. The footage was primarily shot by the three characters on a Hi8 camcorder, enhancing the amateur feel and consequently embedding the sense that these personalities on screen are genuinely filming a documentary. Further detaching the cast from the facets of their actions belonging to a broader project is the actions of genuine contention arisen by the crew behind the scenes.

As the actors would essentially be left alone to record the loose script, the cast would be given clues as to where their following location would be via secret messages located inside 35mm film cans. This would often lead to the trio becoming lost and hostile with one another about their directions. A few of these squabbles were left in the final cut of the film but cut around to match the context of being lost amidst the horror of the plot. The directing duo would also make the characters traverse extensive journeys throughout the day, heightening the already low mood and making them irate. As one last push to both blur the lines of fiction and reality and weaponise what the filmmakers coined ‘method filmmaking’, when the night drew close, and the cast could unwind, the crew would show up unannounced and play creepy pranks, all before whittling down their food supply each day.

The sick, twisted, and undoubtedly cruel tactics resulted in raw footage that, regardless of the scripted mythos of witchery, was an authentic portrayal of people reaching the brink, hitting their peak and unleashing wraths of turmoil and anger over the dreaded scenario. With such a defiant approach to achieving the filmic goal, it is no surprise that the immediate reception was primarily one of praise, with many outlets applauding the innovativeness and ‘less is more’ approach towards the antagonistic force.

On the other hand, the media also reported on the buzz the film received at its premiere at the Sundance Film Festival (1999), where audience members were fainting and vomiting at the dizzying handheld, motion-sickness-provoking cinematography. However, as any horror fan knows, festival drama and antics over the gruesomeness of horror is a good sign of quality gnarly, horrid and shocking filmmaking. As the film’s now notorious reception was building, a secondary force of conversation was budding amongst audiences.

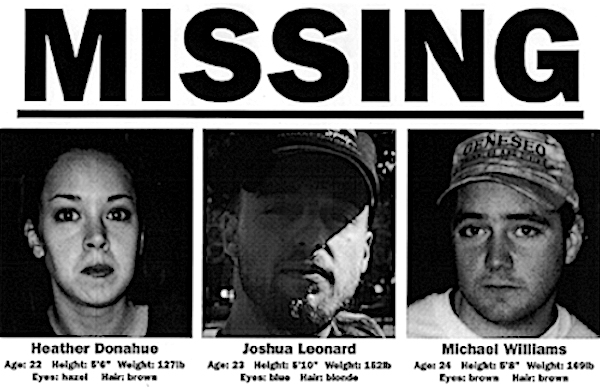

A key detail in The Blair Witch Project’s reputation is its marketing campaign. Prior to the premiere, the film launched a website which featured fake police reports and newsreel-esque interviews seeking to find the ‘missing’ students. However, the most ‘alarming’ snippet showcased a missing poster of Heather, Michael and Josh, complete with the standard height, age and weight typical to a genuine missing person flyer.

It was one thing that the film purported its diegesis to be one of pure authenticity, but if there were any ‘unconvinced’ spectators were not buying the ‘truth’, Myers and Sánchez would keep up the act off-screen, pretending that the film’s festival screenings were motivated by wanting to get the message out there about the disappearances; even going as far to distribute print outs of the missing poster to audience members. The final flourish regards how the official IMDB page listed the performers as “missing, presumed dead”! Although the internet did not have the colloquial sharing aspect nailed to a fine art in terms of sharing and speculating as it does today, the film managed to go ‘viral’.

It took Myrick and Sánchez seven years from the initial idea to the premiere at Sundance, proving that whilst independent cinema can involve intensive labour that is a marathon, not a sprint, indie horror can turn passion and creativity into payoff. In the last twenty-five years, The Blair Witch Project’s reputation is still thriving, with the film spawning comic books, video games and two sequels, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2 (2000) and Blair Witch (2016), as well as an array of parodies, including the criminally underrated Scooby Doo Halloween Special – The Scooby Doo Project (1999).

What comes with such notoriety is a sense of familiarity. Even if a non-horror fan were to come across imagery from the film, they would immediately recognise where the callback originated. It could even be said that those who have never seen the movie can distinguish the continuous references made to the film in pop culture. Think of the infamous extreme close-up of Heather trembling with fear, looking straight into the lens, essentially saying her goodbyes, or the shot of Mike standing, staring at the wall as if in a trance, with Heather screaming bloody murder in the background.

The Blair Witch Project is akin to a landmark, standing proudly in a brimming genre, with its history and legacy granting it a place against all of the greats before and many of the classics yet to come.

You can catch the film Friday 27th September at this years festival, tickets here!

Share this story